Around the year 1400, the French king Charles VI began to exhibit a number of disturbing behaviors that eventually earned him the nickname "Charles the Mad." Among these behaviors, he refused to let anyone touch him and began wearing special clothes with iron rods sewn into them.

The reason? He allegedly believed his body was made of glass and at risk of shattering, making him the first recorded victim of a psychological condition referred to as the "glass delusion."

More than 600 years later, Charles VI's delusion has become the subject of numerous social media posts and popular YouTube videos. For example, in an X post (archived) made on June 6, 2024, a user reposted another, earlier item about the history of anxiety, adding a screenshot of the first two sentences of the Wikipedia page for "Glass delusion." That repost had received around 7,400 reposts and 75,000 likes at the time of this writing.

(X user @Interrobang_2)

The section of the Wikipedia page visible in the repost read:

Glass delusion is an external manifestation of a psychiatric disorder recorded in Europe mainly in the late Middle Ages and early modern period (15th to 17th centuries). People feared that they were made of glass "and therefore likely to shatter into pieces."

The following day, a Tumblr user posted a screenshot of that repost showing both the original post and the Wikipedia screenshot. The Tumblr post had received around 13,700 reblogs and 19,300 likes at the time of this writing.

The X post and the screenshot of it that was shared on Tumblr are the most popular appearances of the glass delusion on social media to date, but they are by no means the first.

The earliest mention of the delusion Snopes was able to track down was a Reddit post made on Jan. 17, 2009, which had the headline "The Glass Delusion" and consisted of a link to the Wikipedia page (the version of the Wikipedia page visible on that date can be accessed here).

Over the following years, the glass delusion was the subject of a relatively steady stream of posts primarily on X and Reddit. Many of these consisted of descriptions of the delusion ranging in length from single sentences to multi-post threads.

Other posts consisted of users simply stating that they were thinking about the glass delusion.

I am never not thinking about the glass delusion pic.twitter.com/pGi6Jkkbor

— Glass Bead Gamer (@GrillPillMax) June 13, 2023

In a few cases, internet users attempted to make humorous memes about the glass delusion, none of which went on to circulate widely.

Charles VI had glass delusion and had iron rods sewn into his clothes to protect himself

byu/YunoFGasai inHistoryMemes

With the exception of the few examples of joke memes, the vast majority of social media posts about glass delusion express genuine interest in and amusement at the delusion, typically without questioning whether it was in fact a real historical phenomenon.

How did the internet develop this interest in a centuries-old mental health disorder? And is the information shared in such posts accurate, in the sense that it reflects the current historical and medical understanding of the glass delusion?

To answer these questions, Snopes dove into the history of the meme as well as the accuracy of online descriptions of the glass delusion.

Slow and Steady Growth

The glass delusion has never had a truly viral moment. Instead, online interest in the historical phenomenon appears to have grown organically since the 2009 Reddit post, which is the earliest securely datable appearance of the glass delusion on social media that Snopes has been able to identify.

One factor that appears to have influenced online interest in the glass delusion is the publication of articles on the disorder by traditional and digital media outlets.

The blog io9 (now part of technology blog Gizmodo) published an article on the glass delusion in September 2014. The following year, in May 2015, the BBC simultaneously released a radio program and corresponding BBC News magazine article about the delusion. History.com followed with their own take in December 2017. In 2018, JSTOR Daily, the public-facing arm of the digital academic library JSTOR, published an article about the glass delusion with links to relevant scholarship in JSTOR's collections.

Around the same time, a number of creators on YouTube began releasing video content about the delusion. The earliest example, produced as part of the official HowStuffWorks account's "Science on the Web" series, was uploaded on July 15, 2015.

The HowStuffWorks video had received around 9,800 views at the time of this writing. Subsequent videos on the topic received significantly higher view counts: A video posted by YouTube account Colossal Cranium in May 2021 has been viewed more than 461,000 times; another, posted by Youtuber Professor Graeme Yorston in July 2022, received around 123,700 views. A more recent video, posted by vlogger Jules Dapper in April 2024, has been viewed around 146,000 times as of this writing.

It's difficult to quantify how much impact any of these articles and YouTube videos had on the public awareness of and interest in the glass delusion. However, there are some signs that each new piece of content helped the topic build momentum online. For example, the list of sources that Dapper included underneath her 2024 YouTube video begins with links to the 2017 History.com article and the 2018 JSTOR Daily piece.

What Historians Have to Say

For the most part, the information about the glass delusion presented in social media posts and popular YouTube videos closely follows research done on the topic by professional historians like Gill Speak, who in 1990 published two separate articles that are still seen as authoritative introductions to the glass delusion.

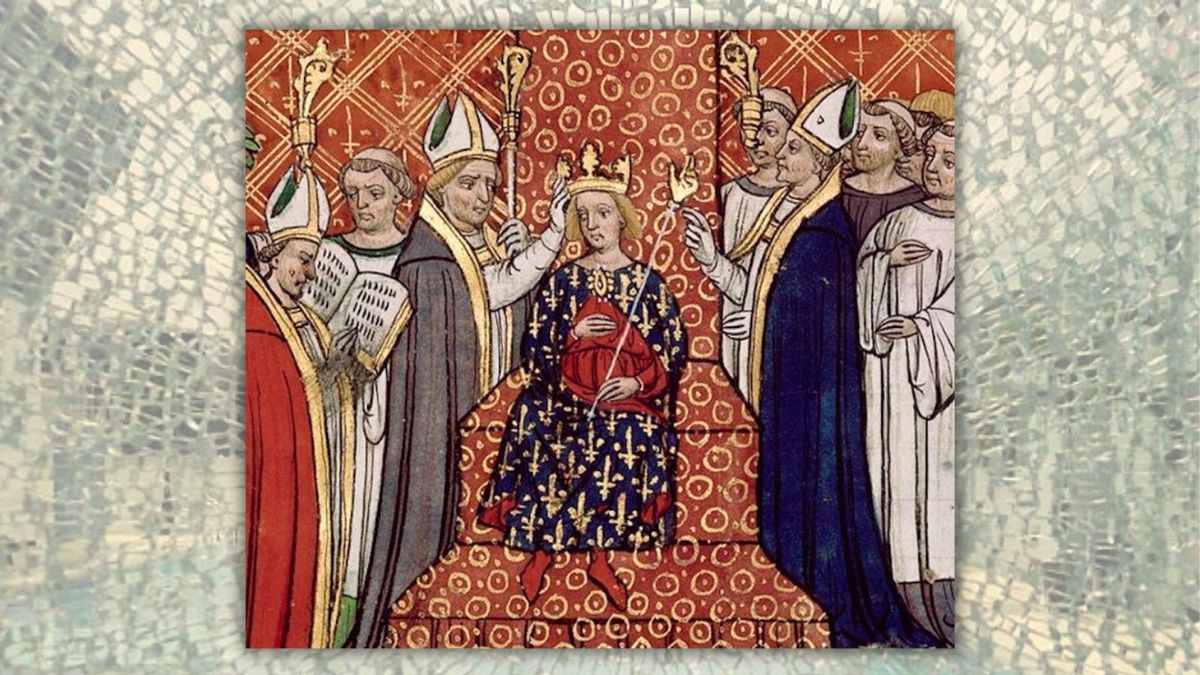

In his articles, Speak walks readers through the medieval and early modern evidence for the glass delusion. The earliest case Speak identifies is Charles VI, who Speak and later authors have retrospectively diagnosed with the glass delusion. The evidence for this diagnosis is a short passage from the "Commentaries" of Pope Pius II, who was born more than 30 years after Charles VI died. The passage reads in full:

Sometimes he [Charles VI] thought he was made of glass and would not let himself be touched. He had steel rods put into his clothing and protected himself in all sorts of ways that he might not fall and break.

This might not be strong evidence by modern standards, but historians have generally accepted Pius' description of Charles VI's symptoms as proof of the first genuine case of glass delusion. Snopes has found no examples of historians arguing against this interpretation.

Aside from Charles VI, Speak's evidence for historical examples of glass delusion falls into two broad categories. The first category consists of accounts written by physicians in the 16th and 17th centuries about anonymous patients, meaning we have very little information about who most historical glass-delusion sufferers were. The most famous of these accounts, which Speak suggests at least some of the other accounts may have been based on, was written by the Dutch physician Levinus Lemnius and reads as follows:

Another [patient] thought that his buttocks were made of glass, so that he did everything while standing, fearing that if he sat, he would break his rump, and the glass would fly into pieces.

There are also a number of fictional accounts of glass delusion, most of which date to the 17th century. The most famous is "The Glass Graduate," a story by "Don Quixote" author Miguel de Cervantes, which was first published in 1613 and focused on a fictional young scholar afflicted with glass delusion.

Many online "deep dives" into glass delusion claim the disorder was a psychological response to the novelty of glass in late medieval and early modern Europe. This explanation does not appear in either of the articles by Speak, who instead thought glass delusion was primarily caused by a pathological response to

However, the idea that glass delusion developed as a result of the increased presence of glass in late medieval and early modern Europe, which is generally attributed to the historian of psychiatry Edward Shorter, is a legitimate theory.

Humans have produced glass objects for around 4,000 years, but technological advances that took place in Venice in the 14th and 15th centuries resulted in an enormous increase in the availability of glass across European markets. These advances also resulted in the availability of new types of glass like cristallo, which was completely colorless and transparent.

Despite the increased availability of glass in the late medieval and early modern period, it was still an expensive luxury product. Some YouTubers, such as Dapper at around the 03:02 timestamp of her video, embedded below, have connected glass's exclusivity to the fact that the disorder only seems to have been reported in wealthy or educated patients.

Although Shorter did not make this exact claim himself, it's a logical connection to draw, and it's not one that any historians have specifically argued against.

Delusions about the Glass Delusion

Although online discussions of the glass delusion are generally decent reflections of the scholarly research into glass delusion, two common claims aren't fully backed by the historical evidence.

The first is the claim that the glass delusion was once "common" among European elites. In fact, only a handful of actual cases are documented in historical sources from the late medieval and early modern period, and most of the patients in these accounts are anonymous. In fact, the only named historical figures that all historians who have written about the glass delusion seem to agree definitely suffered from the condition were Charles VI and Nicole du Plessis, a niece of the 17th-century French statesman Cardinal Richelieu.

A number of popular online accounts of the glass delusion also mention a 19th-century princess, Alexandra of Bavaria, as a sufferer. Unlike Charles VI, Alexandra didn't believe her body was made of glass. Instead, she suffered from the delusion that as a child she had somehow swallowed an entire glass piano, which remained inside her and would shatter if she did not take extreme care regarding her movements and how people touched her.

Even if Alexandra's condition is accepted as a genuine case of glass delusion, that brings the total number of named historical figures who suffered from the glass delusion between the 15th and 19th centuries to three, an average of less than one case per century. Speak, the historian, listed five additional late medieval or early modern cases described by physicians who did not name the patients. Adding those anonymous cases to the total results in an average of only two attested cases per century.

Another common claim that is not backed up by the historical evidence is that cases of glass delusion abruptly disappeared once Europeans grew more accustomed to glass, which may have originally resulted from an over-interpretation of Speak's claim that he was only able to identify "two specific (uncorroborated) cases of the glass delusion" in modern times.

In fact, the glass delusion never disappeared — it's just now considered one of many types of somatic delusion, a common symptom in schizophrenia and other mental disorders. Karl Jaspers, one of the founders of modern psychiatry, wrote that a stereotypical schizophrenic patient might believe "he is a soap-bubble, or that his limbs are made of glass," in his "General Psychopathy," which was first published in 1913.

Around the same time, in 1914, the British psychiatrist Charles Mercier wrote in his "Textbook of Insanity" that delusions such as "that the legs are made of glass … are common enough."

Symptoms that could be described as the glass delusion have been mentioned in similar psychiatric textbooks published throughout the 20th century and well into the 21st, as in the 2022 "Fundamentals of Psychiatry for Health Care Professionals," which lists the belief "my bones are made of glass" as a common somatic delusion among schizophrenic patients.

Through the Looking Glass

Despite exaggerated claims about the historical prevalence of glass delusion and its eventual disappearance, neither of which are fully supported by the evidence, the glass delusion as an online phenomenon has for the most part reflected actual scholarship on the topic.

On social media, this relative accuracy can largely be attributed to the fact that so many posts consist of screenshots of parts of the Wikipedia page for the phenomenon. That's not to say that Wikipedia is a reliable source in itself, but the site's verifiability policy means that much of its "Glass delusion" page consists of simple paraphrases of research on the phenomenon originally published by qualified scholars.

At the same time, Wikipedia's policy of constant, ongoing revision by independent volunteer editors means that errors on the page can, and have been, corrected. A glance at the statistics for Wikipedia's "Glass delusion" page shows that 99 separate editors have made a total of 136 edits to the page since it was created in 2008. Graphed over time, these edits show continued attention to the page as the glass delusion's online profile grew.

(Wikipedia/XTools.org)

A specific example of one of these edits illustrates how, at least in the case of the glass delusion, increased online attention to the page's claims can result in improved accuracy. At the end of her April 2024 Youtube video, Dapper points out that while researching the glass delusion she noticed that there was no real historical evidence that one of the figures listed on Wikipedia's "Glass delusion" page, the Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, ever suffered from the disorder. Not long after Dapper's video went live, a Wikipedia editor deleted the paragraphs on Tchaikovsky from the page.

Ultimately, the glass delusion does not seem to have become a mainstay of internet culture through any one "viral" moment.

Instead, interest in the historical mental disorder appears to have grown organically, reinforced by the publication in mainstream newspapers and magazines as well as special interest blogs of articles citing legitimate historical research. The content of these articles has been interpreted and amplified online through a number of popular YouTube videos about the glass delusion as well as through the Wikipedia page on the topic, which has been edited to remove unsubstantiated information as interest in the glass delusion has grown.